|

|

|

|||||||||

|

How many of you have had a burning desire to visit the United States Supreme Court? My own interest began with an invitation from Karen Raschke to join The Center for Reproductive Law and Policy for a thank-you luncheon at the Sewall-Belmont House, following oral arguments on the Supreme Court case: Ferguson v. City of Charleston.

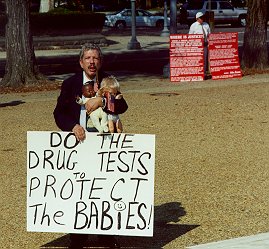

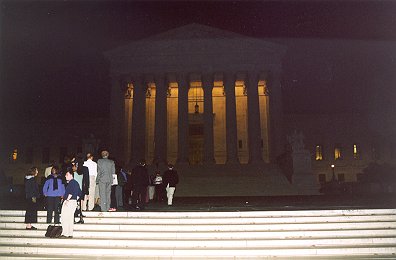

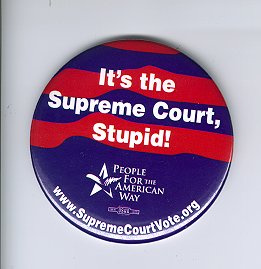

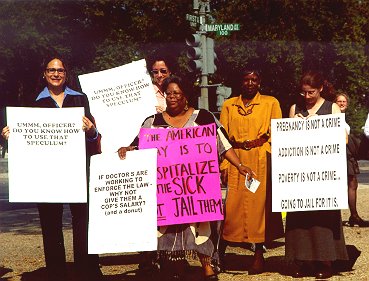

This invitation was accompanied with a byline about the case by Joan Biskupic of USA Today and was followed with the suggestion that I might want to spend the night on the steps of the Supreme Court in order to get into the argument on Wednesday. For all of you night owls out there, this might not seem like much of a problem. But I was very happy to learn later that, rather than showing up at 7 p.m. the night before, I need show up at only 5 or 6 a.m. on Wednesday, October 4, 2000, the morning of the event. "All oral arguments are open to the public, but seating is limited and on a first-come, first-seated basis. Before a session begins, two lines form on the plaza in front of the building. One is for those who wish to attend an entire argument, and the other, a three-minute line, is for those who wish to observe the Court in session only briefly" (Visitor's Guide to Oral Argument, Supreme Court of the United States, September 1999). [Actually, there is also a third line for attorneys and, if you know the right person, you might be able to actually score a reserved seat.] I slept over in suburban Maryland the night before and reserved a cab to take me into Washington, D.C. for 4:30 a.m. All went well until I found that neither the cab driver nor I knew the address of the Supreme Court. Nor did the District policeman whom we met know where the Supreme Court was located, but he did have a map. When I finally arrived at 5:30 a.m., there were already 37 people in front of me, a few who had been there since 3:30 a.m.  Most of the people that I met while waiting to hear the case were either practicing attorneys or law students. And, for the students at least, pulling an all-nighter sounded like a matter of routine.  Seating for the line of people wishing to attend the entire argument did not begin until 9:30 a.m. By this time, the line was down the street and around the corner, with only fifty seats available for non-reserved tickets. Some of these people were standing in line for a second case to be heard that morning. But many people who had waited in order to hear the first case could not get in.  Upon entering the Supreme Court building, you go through a security check-point and again as you enter the courtroom. Weapons or other dangerous or illegal items are not allowed on the grounds or in the building. And the following items are not permitted "when the Court is in session: cameras, radios, pagers, tape players, cell phones, tape recorders, other electronic equipment, hats, overcoats, magazines and books, briefcases and luggage. Notetaking is not permitted. Sunglasses, identification tags (other than military), display buttons and inappropriate clothing may not be worn. A checkroom is available on the first floor to check coats and other personal belongings" (Visitor's Guide to Oral Argument, Supreme Court of the United States, September 1999).  A number of people in line brought a change of clothes to wear once they entered the courtroom. I checked my camera, my keys (with a pin-knife on the key ring), my cellular, and my "It's the Supreme Court, Stupid!" button which I thought might have been considered inappropriate even had buttons been allowed. ["It's the Supreme Court, Stupid!" is part of a campaign launched by People For the American Way to educate the public about the importance of the upcoming Presidential election on determining who will be appointed to the United States Supreme Court.] The lawn chair that I brought to sit in could not be checked and had to be abandoned. Upon entering the courtroom, I was in no way prepared for the gravity of the occasion. A case selected for oral argument "usually involves interpretations of the U.S. Constitution or federal law. At least four Justices have selected the case of being of such importance that the Supreme Court must resolve the legal issues" (Visitor's Guide to Oral Argument, Supreme Court of the United States, September 1999). Justices "grant review in approximately 100-120 of the more than 7,000 petitions filed with the Court each term" (Visitor's Guide to Oral Argument, Supreme Court of the United States, September 1999). "So far, the justices have accepted roughly two-thirds of the 70 to 80 cases they are expected to hear and decide between now and the end of June" (Warren Richey, The Christian Science Monitor, October 2, 2000).  On October 4, 2000, the United States Supreme Court heard arguments in Ferguson v. City of Charleston, a challenge to a South Carolina drug-testing policy created by the police, local prosecutors, and a public hospital where poor women received prenatal care. While the arguments were interesting (particularly questions raised about doctors being used as agents of the police) and the policies being considered consequential (CLRP and the Women's Law Project have argued that the scheme is dangerous, counterproductive, and unconstitutional), I was mostly struck by the hallowedness of the occasion. As an outsider, I could only guess from the questions asked by the Justices about the alliances and voting patterns within the Supreme Court. Sitting far to the back of the court, I had to listen and watch intently to pick up the thread and the nuances of the case. At the first hint of noise, court employees moved quickly to hush the crowd, except of course laughter when one of the Justices said something that was obviously funny. Sitting in the courtroom, I recovered my own sense of reverence: not the kind I experience as an adult (which is often accompanied with some skepticism about human events) but the kind I experienced as a child at church. Leaving the courtroom, the spell was broken. Attorneys made their statements.  The plaintiffs held up signs.  A lone demonstrator was flanked by someone with another agenda altogether.

And I myself proceeded over to Sewall-Belmont House for discussion of the case and a wonderful luncheon. My gratitude to all of the folks over at The Center For Reproductive Law and Policy, to The Women's Law Project, to South Carolina Advocates for Pregnant Women, to the seventy-five organizations and individual medical researchers who joined in amicus briefs, and to the 10 brave women who filed against Charleston, South Carolina and are looking out for the rights of us all. For even more on the case, see CRLP Press Release, When Should Doctors Serve as Agents of the Police?, Justices Weigh Hospital, Police Checking of Patients, and Policing Pregnancy. For a recent piece on oral arguments before the Supreme Court, see Arguing on High: An Appealing Practice. If you have comments about this case or about your own visit to

the United States Supreme Court, please send them to george@loper.org and

the most representative will be posted with full attribution.

|